The birth of modern science was not a clean break from ancient “superstition.” It was a continuation. A translation. A rebranding of something far older than Babylon itself.

Newton’s Hidden Library

When Isaac Newton died in 1727, his executors found something troubling in his papers.

The man celebrated as the architect of modern physics, the discoverer of gravity, the inventor of calculus, the father of optics, had written more words on alchemy than on all his scientific work combined. Over one million words. Notebooks filled with coded symbols, references to the Emerald Tablet of Hermes Trismegistus, experiments seeking the Philosopher’s Stone.

The papers were quietly suppressed. For two centuries, Newton’s alchemical obsession was treated as an embarrassing aberration. The great rational mind’s secret hobby. Best forgotten.

When the manuscripts finally surfaced at a Sotheby’s auction in 1936, the economist John Maynard Keynes purchased a large collection. After studying them, he delivered a verdict that still unsettles the modern mind:

“Newton was not the first of the age of reason. He was the last of the magicians, the last of the Babylonians and Sumerians, the last great mind which looked out on the visible and intellectual world with the same eyes as those who began to build our intellectual inheritance rather less than ten thousand years ago.”

The last of the Babylonians.

Keynes had stumbled onto something the Royal Society’s official histories had carefully obscured. The birth of modern science was not a clean break from the “superstition” of the past. It was a continuation. A translation. A rebranding of something far older than Babylon itself.

The Watchers’ Curriculum

The 81-book Ethiopian canon preserves what Rome excised. In 1 Enoch, chapters 6-8, we find the original syllabus, the curriculum the Watchers taught humanity before the Flood:

“And Azazel taught men to make swords, and knives, and shields, and breastplates, and made known to them the metals of the earth and the art of working them, and bracelets, and ornaments, and the use of antimony, and the beautifying of the eyelids, and all kinds of costly stones, and all coloring tinctures.”

“Semjaza taught enchantments and the cutting of roots; Armaros taught the resolving of enchantments; Baraqiel taught astrology; Kokabiel taught the constellations; Ezeqeel taught the knowledge of clouds; Araqiel taught the signs of the earth; Shamsiel taught the signs of the sun; and Sariel taught the course of the moon.”

This is not a list of random skills. It is a precise inventory of what later traditions would call the Hermetic sciences: metallurgy, cosmetics (the transformation of appearance), astrology (the reading of celestial signs), pharmacology (the cutting of roots), and the resolution of enchantments, what we might call chemistry, the manipulation of material substances through invisible forces.

The text is explicit about the source. This knowledge did not arise from human observation or incremental discovery. It was transmitted by rebellious celestial beings who abandoned their proper station. The Watchers did not invent this knowledge. They revealed what humans were not yet meant to possess.

The term the text uses is telling: they taught humanity the secrets of heaven.

Here is the Enochic indictment: The knowledge itself was not evil. The timing was catastrophic. Humans received power without the wisdom to wield it. The result was not enlightenment but corruption. “Widespread wickedness arose, and they engaged in fornication, were led astray, and corrupted all their ways.”

Capability without character. The pattern repeats.

Fast forward three millennia.

In 1460, a Greek manuscript arrives in Florence from Macedonia, delivered to Cosimo de’ Medici, the banker-prince who rules the city through gold rather than title. The manuscript contains the Corpus Hermeticum: dialogues attributed to Hermes Trismegistus, a figure the Renaissance believed to be an ancient Egyptian sage who lived in the time of Moses.

Cosimo was financing Marsilio Ficino’s translation of Plato’s complete works, the first time Plato would be available in Latin to Western readers. But when the Hermetic texts arrived, Cosimo ordered Ficino to drop Plato immediately.

The dying patriarch wanted to read Hermes before he died. Plato could wait. Hermes could not.

Why the urgency? Because the Renaissance believed Hermes was older than Plato. Older than Moses. Perhaps as old as the Flood itself. If you wanted to recover the prisca theologia, the original theology given to humanity at the beginning, Hermes was the source.

Ficino completed the translation in 1463. It spread through Europe like fire through dry timber. By 1500, over forty manuscript copies and twenty-four printed editions. Learned men across Christendom began studying what Ficino called the “ancient theology,” a tradition linking Hermes to Orpheus to Pythagoras to Plato, all pointing toward Christianity as their fulfillment.

What did the Corpus Hermeticum actually teach?

The same curriculum as the Watchers: astral magic (drawing down celestial influences), the manipulation of material substances through invisible sympathies, the transformation of base matter into higher forms, and the ultimate promise, the deification of humanity through gnosis.

The opening line of the first treatise states it plainly: “I am Poimandres, the Mind of absolute power. I know what you wish, and I am with you everywhere.”

The Hermetic promise was not passive contemplation but active transformation. Man could become like God. Not through obedience to divine command, but through the acquisition of divine knowledge.

The Watchers’ curriculum had found a new classroom.

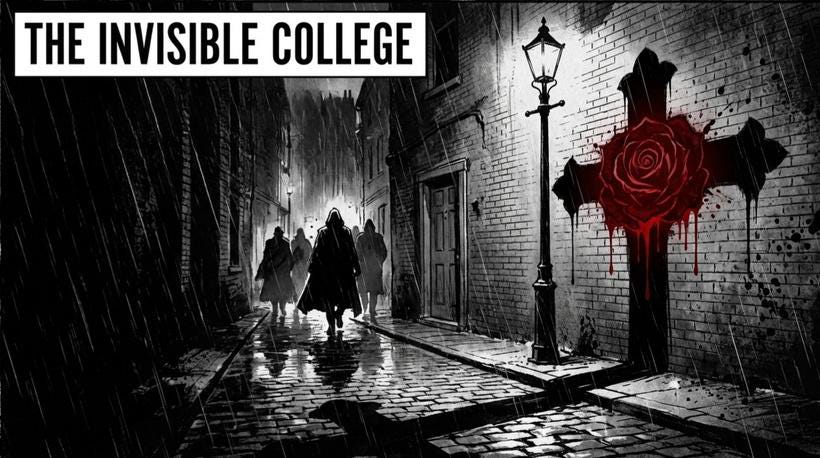

In 1614 and 1615, two anonymous manifestos appeared in Germany announcing the existence of a secret brotherhood: the Fraternity of the Rose Cross.

The Fama Fraternitatis told the story of Christian Rosenkreutz, a German who had traveled to the East, to Damascus, to Fez, and learned the secrets of the ancient sages. He returned to Europe and founded a brotherhood dedicated to healing, hidden knowledge, and the reformation of all arts and sciences.

Whether the Rosicrucians actually existed as an organization remains debated. Their influence does not.

The manifestos described an “Invisible College” of enlightened adepts working to transform human knowledge. This phrase would become operational.

In England, a generation of scholars began meeting informally in the 1640s, driven underground by the chaos of the Civil War. They called themselves, with explicit Rosicrucian reference, the “Invisible College.” Robert Boyle used the term in his correspondence: “The cornerstones of the Invisible (or as they term themselves the Philosophical) College, do now and then honour me with their company.”

The London branch of this network met under the guidance of Samuel Hartlib, described by contemporaries as a “famed Hermeticist” with documented connections to the “shadowy Rosicrucian Brotherhood.” Hartlib’s correspondents included alchemists and practitioners of the “chemical philosophy” that traced its lineage to Paracelsus and, through him, to Hermes.

On November 28, 1660, twelve men met at Gresham College in London after a lecture by the astronomer Christopher Wren. They resolved to form “a Colledge for the Promoting of Physico-Mathematicall Experimentall Learning.”

The Invisible College was becoming visible.

Within months, King Charles II granted them a royal charter. The Royal Society was born.

Consider the founding circle:

Elias Ashmole (1617–1692). One of the Royal Society’s founders. Also the second man on record to be initiated as a Freemason in England (1646). His major work, Theatrum Chemicum Britannicum (1652), was an anthology of English alchemical poetry. The book opens with a quotation from the Fama Fraternitatis. Ashmole transcribed John Dee’s Monas Hieroglyphica for his own study and later acquired Dee’s “spiritual diaries,” records of his angel communications.

Robert Boyle (1627–1691). Celebrated as the “father of modern chemistry” for his 1661 work The Sceptical Chymist. Less celebrated: Boyle’s extensive alchemical pursuits, which his early biographers Henry Miles and Thomas Birch actually destroyed, fearing they would “tarnish his reputation as a scientist.” Boyle studied under the American alchemist George Starkey and replicated the experiments of Jan Baptist van Helmont, the Flemish Hermeticist. His supposed “rejection” of alchemy in The Sceptical Chymist was actually a rejection of Aristotelian chemistry in favor of a corpuscular theory borrowed directly from alchemical atomism.

Sir Robert Moray (c. 1607–1673). The man who told King Charles II about the new society and secured royal approval. Moray was initiated as a Freemason in 1641 while serving in the Scottish army, one of the earliest documented Masonic initiations.

Isaac Newton (1642–1727). President of the Royal Society from 1703 to 1727. As documented by the Keynes collection and the ongoing “Chymistry of Isaac Newton” project at Indiana University, Newton wrote approximately one million words on alchemy. His notebooks reference the Emerald Tablet, the works of Philalethes (George Starkey’s alchemical pseudonym), and Nicholas Flamel. Newton believed he was recovering ancient wisdom, the same prisca theologia that Ficino had sought.

For Newton, Hermeticism was not opposed to science but its deepest foundation.

Here is the maneuver: The Royal Society did not reject occult knowledge. It reclassified it.

The alchemical quest to transform base metals into gold became “chemistry,” the study of material transformation through invisible forces (now called “bonds” and “reactions”).

The Hermetic principle that celestial bodies influence earthly events became “physics,” the study of forces acting at a distance. Newton’s gravity was directly inspired by his reading of alchemical “sympathies.”

The Watcher teaching that the stars encode information became “astronomy,” observation stripped of interpretation.

The key move was philosophical, not empirical. Boyle’s “mechanical philosophy” proposed that all phenomena could be explained by the motion of corpuscles obeying mathematical laws. This was not a discovery. It was a decision.

The spiritual causes that alchemists invoked, the active principles, the vital spirits, the influences of celestial intelligences, were declared inadmissible. Only material causes operating through mechanical contact were permitted.

This was not the triumph of observation over superstition. It was a methodological choice to exclude certain categories of explanation from public discourse while continuing to pursue them privately.

Newton published the Principia. He did not publish his alchemical notebooks.

Boyle published The Sceptical Chymist. His biographers burned his alchemical papers.

The split was not between knowledge and ignorance. It was between public and esoteric.

The Royal Society’s founding charter prohibited discussion of religion and politics at meetings. This was presented as neutral rationality. It was actually a firewall, protecting the inner work from external scrutiny while the outer work gained institutional legitimacy.

The word “transhumanism” was coined in 1957 by Julian Huxley, grandson of Thomas Henry Huxley (”Darwin’s Bulldog”), brother of Aldous Huxley (author of Brave New World). Julian was the first director of UNESCO, president of the British Eugenics Society from 1959–1962, and a founding member of the World Wildlife Fund.

In his 1957 essay, Huxley defined the project: “Man remaining man, but transcending himself, by realizing new possibilities of and for his human nature.” He called it a “new ideology,” an updated framework for the “continuing adventure of human development” through deliberate technological and genetic intervention.

The continuity is explicit. Huxley’s transhumanism grew directly from his decades of work in eugenics, the “science” of improving human genetic stock through selective breeding. The ideas came from the 1920s work of J.B.S. Haldane (Daedalus: Science and the Future, 1923) and J.D. Bernal (The World, the Flesh and the Devil, 1929), both members of what historians call the “British transhumanist” circle of the interwar period.

What Haldane predicted in 1923: “Every great advance... will first appear to someone as blasphemy or perversion, indecent and unnatural.” He was particularly interested in ectogenesis (artificial wombs), eugenics, and genetic modification.

The Watchers’ curriculum updated for the industrial age.

Contemporary transhumanists, Nick Bostrom, Ray Kurzweil, Max More, typically do not emphasize Huxley in their origin stories. They prefer to cite Prometheus, Gilgamesh, and the “perennial human dream of perfectibility.” This is the Hermetic move again: the claim of ancient wisdom, the erasure of immediate genealogy, the presentation of continuity as novelty.

But the goal remains constant across millennia: the transformation of humanity into something greater through acquired knowledge.

The Watchers taught “the secrets of heaven” to beings who were not ready.

The Hermeticists sought the prisca theologia that would restore humanity to divine status.

The Royal Society founders pursued the transmutation of matter and the extension of life.

The transhumanists pursue “radical life extension,” “cognitive enhancement,” and the emergence of a “posthumanity” that transcends biological limits entirely.

The promise is always the same: You will be like God.

The Enochic analysis offers a diagnosis that modern secularism cannot provide: The knowledge is not the problem. The sequence is the problem.

The Watchers did not invent metallurgy or astrology or pharmacology. They revealed what God had intended humanity to discover gradually, through maturation, through the cultivation of wisdom alongside power. The forbidden knowledge was knowledge given before its time. Capability without corresponding character.

This is the grammar of Creation: Power follows character. Revelation matches readiness.

The fruit of the Tree of Knowledge was not forbidden forever, only forbidden first. Eat of the Tree of Life, then the Tree of Knowledge. Not the reverse.

The Hermetic tradition, from ancient Alexandria through Renaissance Florence to the Royal Society, inverts this order. It promises divine knowledge as the means to divine nature. Know first, then become.

This is the Watcher pedagogy: transmission without transformation, power without purity, secrets without sanctification.

The result is what we now call “modernity”: a civilization with godlike powers and adolescent character. We can split atoms but cannot govern our appetites. We can edit genomes but cannot educate our children. We can communicate instantaneously across the globe but cannot converse with our neighbors.

The Watcher pattern produces technological mastery and spiritual collapse in exact proportion.

The Narrow Path

The Covenant path is not anti-knowledge. It is ordered knowledge. Character before capability. Wisdom before technique. The fear of the Lord as the beginning of wisdom, not its conclusion, not its competitor, but its prerequisite.

When Paul warned the Corinthians that “knowledge puffs up, but love builds up,” he was not rejecting knowledge. He was identifying its proper position in the sequence.

When Solomon asked for wisdom rather than wealth or power, he was demonstrating the correct order of acquisition.

When Christ told His disciples that the Spirit would guide them into “all truth,” He was promising the same comprehensive knowledge the Hermeticists sought, but through a different door.

The transhumanist promise, that technology will deliver us into posthuman divinity, is the Watcher promise in silicon clothing. It will produce the same result: giants who consume everything around them, a generation of power without peace, and eventually, a flood.

The narrow path is not narrower because it offers less. It is narrower because it requires more: the cultivation of character before the acquisition of capability, the submission of knowledge to wisdom, the recognition that we are creatures before we are creators.

All knowledge belongs to God. The question has never been whether humanity should possess it, but when, how, and through whom.

The sorcerer’s succession, from the Watchers through Hermes through the Royal Society to the transhumanist laboratory, offers one answer.

The Covenant offers another.

The choice, as always, is before us.

Visit https://kingdomcode.substack.com and https://midnightsignals.net for more.